Phishing Attack Types

Understanding Phishing Attack Types: A Comprehensive Guide

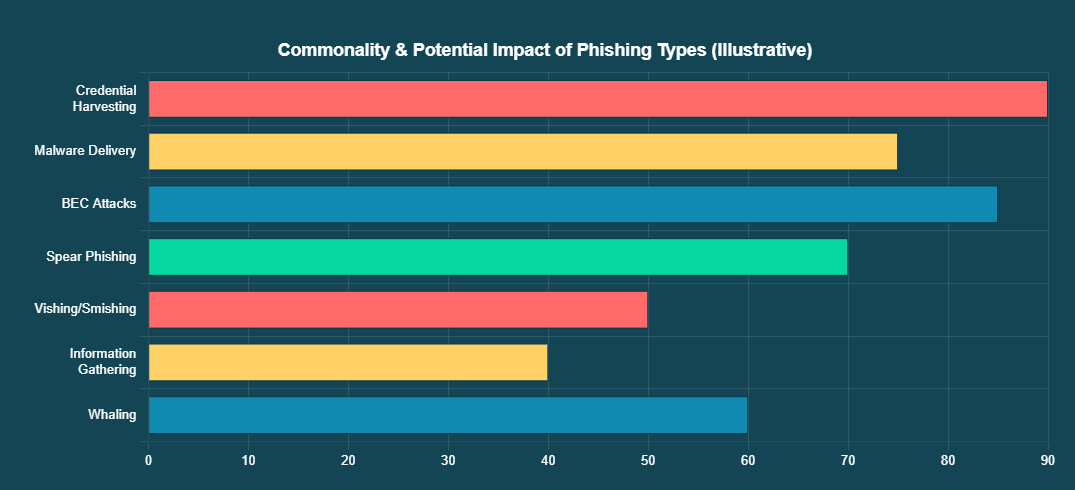

Phishing is a pervasive cyber threat that relies on deception to trick individuals into revealing sensitive information or taking actions that compromise their security. While often associated with fake login pages, phishing encompasses a variety of tactics, each with a distinct objective. This blog post breaks down some of the most common types of phishing attacks.

1. Information Gathering (Reconnaissance Phishing)

This type of phishing attack focuses on collecting data about a target without necessarily requiring them to click a malicious link or download an attachment immediately. The primary goal is to verify the existence and activity of an email address and gather intelligence that can be used to craft more sophisticated and convincing attacks later.

How it Works:

Email Validation: Attackers send emails to a large list of addresses to see which ones are active. If an email is opened or a response is received, it confirms the mailbox is in use.

Data Collection: If a user responds, even innocently, information can be gleaned from their email signature (job title, phone number, company details), response time, and other personal or professional data. This information is invaluable for tailoring future, more targeted attacks.

Example:

An attacker might send a seemingly innocuous email, perhaps a generic “delivery notification” or a “survey invitation,” without any malicious links or attachments. The mere act of opening the email, or a simple reply, can signal to the attacker that the email address is active and monitored by a human.

Sample Reconnaissance Email:

Tracking Pixels: A Stealthy Reconnaissance Tool

To gather information silently, attackers often employ a technique involving tracking pixels.

What’s a Tracking Pixel?

A tracking pixel (also known as a web beacon, 1x1 pixel, or pixel tag) is a tiny, often transparent, 1x1 pixel image embedded in an email or web page. It’s usually invisible to the naked eye. When you open an email or load a webpage containing a tracking pixel, your client (email program or web browser) sends a request to the server where the pixel is hosted to download that image. This request is what provides the information to the attacker.

How Hackers Use Tracking Pixels in Phishing:

Validating Email Addresses (Active User Identification):

This is perhaps the most common and immediate use. When a hacker sends out a large volume of phishing emails, they don’t know which email addresses are active and which are defunct. By embedding a tracking pixel in the email, they can:

Confirm Deliverability: If the pixel is loaded, it means the email successfully landed in an inbox and was opened.

Identify Active Users: More importantly, it tells the hacker that a human user is actively engaging with that email address. This makes that email address a more valuable target for future, more sophisticated attacks.

Gathering Victim Information:

While not as detailed as information gathered from a successful credential compromise, tracking pixels can still provide valuable insights:

IP Address and Approximate Location: When the pixel is loaded, the attacker’s server logs the IP address of the device opening the email. This can give them a general idea of the recipient’s geographical location.

Device and Browser Information: The HTTP request to load the pixel can also include information from the user-agent string, such as the operating system, email client, or web browser being used. This helps attackers tailor future attacks (e.g., crafting exploits for specific software vulnerabilities).

Time of Opening: The server logs the exact time the email was opened. This can help attackers understand user behavior patterns (e.g., when a target is most active).

Email Open Rates: For broader phishing campaigns, tracking pixels help attackers measure the effectiveness of their campaigns by showing them how many recipients are opening their malicious emails.

2. Credential Harvesting

Credential harvesting is a technique where hackers attempt to steal legitimate login information, such as usernames and passwords, from unsuspecting victims. The goal is to gain unauthorized access to their accounts, systems, or networks. This is often the initial step in a larger, more sophisticated cyberattack, leading to data theft, financial fraud, or system disruption.

How it Works:

Impersonation: The attacker pretends to be a trusted entity. This could be a bank, a well-known company (like Microsoft, Google, or a popular social media platform), a government agency, or even someone within the victim’s own organization (like IT support or a senior executive).

Deceptive Communication: The attacker sends a phishing email, text message (smishing), or makes a phone call (vishing) designed to create urgency, fear, or a sense of curiosity. The message often contains a call to action, such as “Your account has been compromised, click here to verify,” “Your invoice is ready, view securely,” or “Important security update required.”

Malicious Link/Attachment: The communication usually contains a link that, when clicked, redirects the victim to a fake website. Alternatively, it might contain a malicious attachment that, if opened, installs malware (like a keylogger) on the victim’s device.

Fake Login Page: The fake website is meticulously designed to mimic the legitimate site it’s impersonating. It will often have the same logos, colors, and layout, and, crucially for credential harvesting, it will include a login form asking for the victim’s username and password.

Credential Capture: When the victim enters their credentials into this fake login page, the information isn’t sent to the real service; instead, it’s sent directly to the attacker. The fake page might then redirect the user to the real website, display an error message, or simply refresh, leaving the victim unaware that their credentials have been stolen.

Example:

You receive an email claiming to be from your bank, stating your account has been locked due to suspicious activity. You click a link that takes you to a website looking identical to your bank’s login page. After entering your username and password, the page might show an error or redirect you to the real bank site. Unbeknownst to you, your credentials have been sent to the attacker.

3. Malware Delivery

Malware delivery in phishing refers to the technique where hackers use phishing tactics to trick victims into downloading and installing malicious software (malware) onto their devices. Unlike credential harvesting, where the goal is to steal login information, the primary objective of malware delivery is to gain control over the victim’s system, steal data directly from it, encrypt files for ransom, or use the device as part of a botnet.

How it Works:

The process of malware delivery via phishing typically follows these steps:

Deceptive Communication: Similar to credential harvesting, the attack starts with a phishing email, text message, or other form of communication designed to lure the victim. The message is crafted to appear legitimate and trustworthy, often impersonating a known entity.

Malicious Payload: Instead of a link to a fake login page, the communication contains an element that, when interacted with, delivers the malware. This is commonly:

Malicious Attachment: An attached file (e.g., a PDF, Word document, Excel spreadsheet, ZIP archive, or executable file) that contains the malware.

Malicious Link (Drive-by Download): A link that, when clicked, automatically downloads the malware in the background (a “drive-by download”) or redirects the user to a compromised website designed to exploit vulnerabilities in their browser or software to install malware without their explicit consent.

Social Engineering: The attacker uses social engineering to persuade the victim to open the attachment or click the link. This often involves creating a sense of urgency, curiosity, or obligation.

Execution: Once the victim opens the malicious attachment or lands on a drive-by download site, the malware is executed. This can happen silently in the background or require the user to enable macros (in documents) or grant permissions for an installation.

Infection: The malware then infects the system, carrying out its intended malicious activity (e.g., encrypting files, stealing data, installing a backdoor, creating a botnet).

Example:

You receive an email with a subject like “Urgent: Your Pending Invoice” and an attached file named Invoice_Q3_2025.doc. When you open the document, a security warning prompts you to “Enable Content” to view it properly. If you click “Enable Content,” malicious macros embedded in the document execute, silently downloading and installing ransomware that encrypts your files and demands payment.

Sample Malware Delivery Email:

4. Spear Phishing

Spear phishing is a highly targeted and customized form of phishing. Unlike broad phishing campaigns that cast a wide net, spear phishing attacks are meticulously crafted for a specific individual or organization, leveraging personal information to increase their credibility and success rate.

How it Works:

- Extensive Research: Attackers conduct thorough reconnaissance on their target, gathering details about their job, colleagues, interests, recent activities, and company structure from public sources (social media, company websites, news articles).

- Personalized Content: The phishing email or message is highly personalized, often referencing specific projects, names, or events that would be familiar to the target. This makes the email appear incredibly legitimate.

- Leveraging Trust: The attacker often impersonates someone the target knows and trusts, such as a colleague, manager, vendor, or even a family member.

Example:

An employee receives an email seemingly from their direct manager, with the subject line “Quick Review: Q4 Project Budget.” The email references a specific project the employee is working on and asks them to review an attached “revised budget spreadsheet.” The attachment is actually a malicious file designed to install a keylogger, allowing the attacker to steal the employee’s corporate credentials.

5. Whaling

Whaling is a specialized form of spear phishing that specifically targets high-profile individuals within an organization, such as CEOs, CFOs, or other senior executives. These attacks are designed to trick powerful targets into authorizing significant financial transfers or revealing highly sensitive corporate information.

How it Works:

- High-Value Targets: Attackers focus on individuals with significant authority and access to critical company assets or funds.

- Sophisticated Impersonation: The impersonation is often extremely convincing, potentially mimicking legal documents, urgent executive requests, or sensitive internal communications.

- Large Financial Stakes: The goal is typically to initiate large wire transfers or gain access to confidential financial data.

Example:

A CFO receives an email that appears to be from the CEO, with the subject “Urgent Wire Transfer - Acquisition Details.” The email states that a critical acquisition is underway and requires an immediate, confidential wire transfer to a specific account. The sense of urgency and the high-level sender pressure the CFO to act quickly without proper verification, leading to a fraudulent transfer of company funds.

6. Vishing, SMiShing, and Quishing

These are variations of phishing that utilize different communication channels beyond traditional email.

Vishing (Voice Phishing):

- How it Works: Attackers use phone calls to trick victims. They might impersonate bank representatives, tech support, or government officials, attempting to extract sensitive information over the phone or direct the victim to a malicious website.

- Example: You receive a call from someone claiming to be from your bank’s fraud department, stating there’s suspicious activity on your account. They ask you to “verify” your account number, PIN, or online banking password over the phone.

SMiShing (SMS Phishing):

- How it Works: Attackers send malicious SMS (text) messages containing deceptive links. These links often lead to fake login pages or sites that trigger drive-by downloads.

- Example: You receive a text message that looks like it’s from a shipping company, saying “Your package delivery has been delayed. Click here to reschedule: malicious link.” Clicking the link takes you to a fake website asking for your personal details or installing malware.

Quishing (QR Code Phishing):

- How it Works: Attackers embed malicious URLs within QR codes. These QR codes might be placed on public posters, fake invoices, or even sent via email. When scanned, the QR code directs the user’s device to a phishing site.

- Example: You see a QR code sticker placed over a legitimate parking meter’s payment instructions. Scanning it takes you to a fake payment portal designed to steal your credit card information.

7. Business Email Compromise (BEC)

Business Email Compromise (BEC) is a highly sophisticated scam that targets businesses, often resulting in significant financial losses. Unlike other phishing types, BEC attacks typically do not involve malicious links or attachments. Instead, they rely heavily on social engineering and impersonation to trick employees into making fraudulent wire transfers or sending sensitive information.

How it Works:

- Email Account Compromise/Spoofing: The attacker either gains unauthorized access to a legitimate company email account (e.g., a CEO’s or CFO’s account) or spoofs an email address to make it appear as if it’s coming from a trusted source within the company or a known vendor.

- Impersonation: The attacker impersonates a senior executive, a trusted vendor, or a legal representative.

- Fraudulent Requests: The attacker sends emails requesting urgent wire transfers to new bank accounts, changes to vendor payment details, or the disclosure of sensitive employee data (e.g., W-2 forms). The requests are often made under the guise of secrecy or urgency.

Example:

An employee in the accounts payable department receives an email seemingly from the CEO, stating, “I need an urgent payment processed to a new vendor for a confidential project. Please wire $50,000 to this account immediately. Do not discuss this with anyone.” The employee, believing it’s a legitimate and urgent request from their CEO, processes the fraudulent wire transfer.

8. Spam

While often annoying, spam refers to unsolicited, irrelevant, or unwanted email messages sent in bulk. While some spam emails can contain phishing attempts, spam itself is not inherently malicious in the same way as the other attack types listed. Its primary intent is often commercial advertising or spreading general unwanted content.

How it Works:

- Mass Distribution: Spammers send out millions of emails to large lists of addresses, hoping a small percentage will open or interact with the content.

- Varied Content: Spam can range from advertisements for products and services to scams, hoaxes, or even political messages.

- Low Personalization: Typically, spam is not personalized and lacks the targeted nature of spear phishing or whaling.

Example:

You receive numerous emails daily advertising questionable health supplements, lottery winnings from a country you’ve never visited, or “get rich quick” schemes. These emails are sent indiscriminately to large lists of email addresses. While some might contain links to malicious sites, many are simply unwanted advertisements.

To get in touch with me or for general discussion please visit ZeroDayMindset Discussion